Following the victory of Joe Biden in the 2020 Presidential Election, one omnipresent controversy was able to escape the limelight this time around: the electoral college. This institution has been the subject of vociferous debate over the years, waxing and waning in the public conscience depending on how well it tracks the popular vote in any given election. This begs the question: if the Electoral College is essentially acting as a poor proxy for the popular vote, why does the Electoral College exist at all when the popular vote is available to be used? To properly answer this question, we must delve into the origins of the Electoral College, its evolution throughout American history, the pros and cons of the system as it currently operates, and what this system means for the future of American politics.

In Section II, Article I, the U.S. Constitution lays out the original plan for the Electoral College, whereby each state receives a number of Electors not exceeding their total number of Senators and Representatives, and these Electors cast votes for President of the United States. Once the votes are tallied, whichever candidate has the plurality of the votes becomes President. Interestingly, nowhere in the Constitution or anywhere else (at the time) does it say that citizens vote for President. Instead, the idea was that each district would vote for an Elector to represent their district. This was not an oversight by the Framers; it was by design. The idea behind this was that knowledgeable people from each state would select the next President, and do so by exercising nonpartisan, fair judgement of the candidates (Williams v. Rhodes, 393 U.S. 23, 43–44 (1968)), not unlike the way that the Cardinals select the new pope.

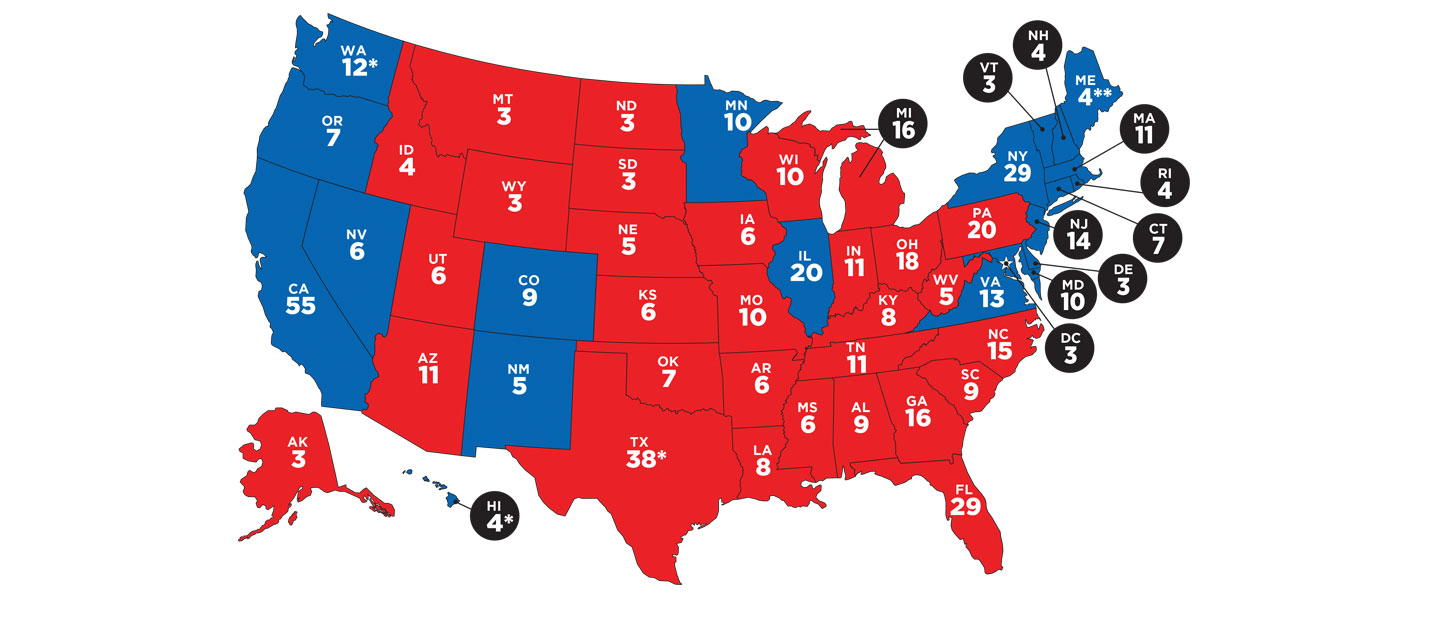

Clearly, the spirit of this procedure has not endured to today. In fact, by 1800, this process was already being corrupted by the emergence of political parties. Furthermore, because the Constitution left the process by which states choose their electors entirely to the states themselves, states quickly deviated from the intended spirit. Despite states testing a few different systems in the early 1800s, by the 1830s, the Electoral College had evolved almost uniformly into the winner-take-all mechanism that we employ today, whereby the winner of the popular vote in each state receives all of that state’s electors. Only Maine and Nebraska differ from the rest, but only marginally. These two states split themselves up into two districts, with the popular vote winner in each district receiving that district’s electoral votes.

In a follow up post, I will be discussing the pros and cons of the current system, and what it means for the future of American politics.